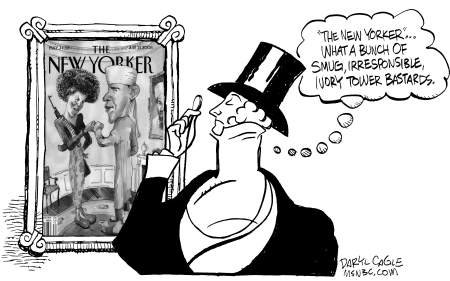

Cable news channels and bloggers are buzzing about The New Yorker magazine cover featuring Barack Obama dressed in Muslim garb and Michelle Obama with an afro and machine gun, doing a “terrorist fist bump” in the Oval Office, while an American flag burns in the fireplace. The cartoon by Barry Blitt drew immediate condemnation from the Obama and McCain camps.

In an interview on the Huffington Post Web site, New Yorker Editor David Remnick argues, “Obviously I wouldn’t have run a cover just to get attention — I ran the cover because I thought it had something to say. What I think it does is hold up a mirror to the prejudice and dark imaginings about both Obamas’ it combines a number of images that have been propagated, not by everyone on the right but by some, about Obama’s supposed ‘lack of patriotism’ or his being ‘soft on terrorism’ or the idiotic notion that somehow Michelle Obama is the second coming of the Weathermen or most violent Black Panthers. That somehow all this is going to come to the Oval Office. “The idea that we would publish a cover saying these things literally, I think, is just not in the vocabulary of what we do and who we are… We’ve run many many satirical political covers. Ask the Bush administration how many.”

Cartoonist Barry Blitt defends the cover by saying, “It seemed to me that depicting the concept would show it as the fear-mongering ridiculousness that it is.” So the cover cartoon is simply an exaggeration of the allegations against the Obamas.

There are rules to political cartoons that allow cartoonists to draw in an elegant, simple, shorthand that readers understand. Exaggeration is a well worn tool of political cartoonists; we use it all the time. I’ve drawn President Bush as the King of England, to exaggerate his autocratic tendencies. I’ve drawn the president as a dog, peeing all over the globe to mark his territory. I exaggerate every day, and I don’t expect my readers to take my exaggerations seriously — but when I draw an absurdly exaggerated political cartoon, I’m looking for some truth to exaggerate to make my point. A typical stand-up comedian will tell jokes about things the audience already knows or agrees with, “it’s funny because it’s true,” or true as the comedian sees it. It is the same for cartoonists — our readers know that we’re exaggerating to make a point we believe in.

There are rules to political cartoons that allow cartoonists to draw in an elegant, simple, shorthand that readers understand. Exaggeration is a well worn tool of political cartoonists; we use it all the time. I’ve drawn President Bush as the King of England, to exaggerate his autocratic tendencies. I’ve drawn the president as a dog, peeing all over the globe to mark his territory. I exaggerate every day, and I don’t expect my readers to take my exaggerations seriously — but when I draw an absurdly exaggerated political cartoon, I’m looking for some truth to exaggerate to make my point. A typical stand-up comedian will tell jokes about things the audience already knows or agrees with, “it’s funny because it’s true,” or true as the comedian sees it. It is the same for cartoonists — our readers know that we’re exaggerating to make a point we believe in.

Cartoonists have a great advantage over journalists in that we can draw whatever we want. We can put words into the mouths of politicians that the politicians never said. Cartoons can be outrageous in their exaggeration; we draw things that never happened, and never could happen — but we have a contract with the readers who understand that we’re drawing crazy things that convey our own views. The New Yorker’s Obama cover fails to keep that contract with readers. Cartoonists don’t exaggerate anything just because we have the freedom to do so; we exaggerate to communicate in a way that our readers understand.

There is no frame of reference in The New Yorker’s cover to put the scene into perspective. Following the rules of political cartoons, I could fix it. I would have Obama think in a thought balloon, “I must be in the nightmare of some conservative.” With that, the scene is shown to be in the mind of someone the cartoonist disagrees with and we have defined the target of the cartoon as crazy conservatives with their crazy dreams.

Since readers expect cartoonists to convey some truth as we see it, depicting someone else’s point of view in a cartoon has to be shown to be someone else’s point of view, otherwise it is reasonable for readers to see the cartoon as somehow being the cartoonist’s point of view, no matter how absurd the cartoon is. That is where The New Yorker’s cover cartoon fails.

I reserve the right to be as offensive as I want in my cartoons, and to exaggerate however I please — but I want my cartoons to work, to be good cartoons. A cartoon that fails to communicate its message in a way that readers understand is nothing more than a bad cartoon.

It would be funny if it weren’t so true. I scanned the Dilbert cartoon (right) from my local Santa Barbara News-Press. A casual reader might read the last panel of the cartoon as the gag (the “awful thing” that is happening to the character is that terrible AM 1290 Santa Barbara News-Press Radio! ARRGH!) But no, it is just Dilbert, proving that he pulls his own weight by generating ad revenue in one of the panels.

It would be funny if it weren’t so true. I scanned the Dilbert cartoon (right) from my local Santa Barbara News-Press. A casual reader might read the last panel of the cartoon as the gag (the “awful thing” that is happening to the character is that terrible AM 1290 Santa Barbara News-Press Radio! ARRGH!) But no, it is just Dilbert, proving that he pulls his own weight by generating ad revenue in one of the panels.

I met Jianping Fan on my recent trip to China. He hails from Guangzhou (formerly Canton) in steamy Southern China. The cartoonists in Guangzhou seem to have more freedom than cartoonists in other parts of China, because they live near Hong Kong where the Chinese are used to seeing much more of the news on TV than elsewhere in China – I think Jianping’s work shows that freedom and is pretty worldly-wise.

I met Jianping Fan on my recent trip to China. He hails from Guangzhou (formerly Canton) in steamy Southern China. The cartoonists in Guangzhou seem to have more freedom than cartoonists in other parts of China, because they live near Hong Kong where the Chinese are used to seeing much more of the news on TV than elsewhere in China – I think Jianping’s work shows that freedom and is pretty worldly-wise.

4) Sergey Elkin works from Moscow and his cartoons appear in Russia, Ukraine and Kazakhstan. As Sergei puts it: “Mostly I draw Putin.”

4) Sergey Elkin works from Moscow and his cartoons appear in Russia, Ukraine and Kazakhstan. As Sergei puts it: “Mostly I draw Putin.”

5) I remember seeing Randy Jones‘ work for many years. His work sits on the borderline between political cartoons and illustrations, which, to my eye, makes them more sophisticated.

5) I remember seeing Randy Jones‘ work for many years. His work sits on the borderline between political cartoons and illustrations, which, to my eye, makes them more sophisticated.

6) Martin Kozlowski is the ringleader of the

6) Martin Kozlowski is the ringleader of the

Steve Nease, Oakville Ontario, Steve is the daily cartoonist for the Oakville Beaver –

Steve Nease, Oakville Ontario, Steve is the daily cartoonist for the Oakville Beaver –

Mike Luckovich, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution

Mike Luckovich, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution

Jerry Holbert, Boston, MA, The Boston Herald

Jerry Holbert, Boston, MA, The Boston Herald

Gary Brookins, Virginia — The Richmond Times-Dispatch

Gary Brookins, Virginia — The Richmond Times-Dispatch

Jim Day,

Jim Day,  DARYL: Editors are always asking us for editorial cartoons that celebrate holidays. More than any other request we get from editors. It may be an outgrowth of editors not wanting controversy, and wanting soft, happy cartoons, and it is interesting for us to gauge just how unhappy they are with cartoonists not giving them what they want.

DARYL: Editors are always asking us for editorial cartoons that celebrate holidays. More than any other request we get from editors. It may be an outgrowth of editors not wanting controversy, and wanting soft, happy cartoons, and it is interesting for us to gauge just how unhappy they are with cartoonists not giving them what they want.  Your cartoons dominated editorial pages on Fathers Day. We got almost no cartoons from other cartoonists on the topic – and we got lots of complaints from editors about that.

Your cartoons dominated editorial pages on Fathers Day. We got almost no cartoons from other cartoonists on the topic – and we got lots of complaints from editors about that.  Your holiday cartoons are a bit different, though. You’re conveying warmth. The typical argument is about soft joke cartoons. Hardly any editorial cartoonist conveys warmth in his cartoons. And clearly, as the syndicate guy here, I can see that editors respond to warmth in cartoons.

Your holiday cartoons are a bit different, though. You’re conveying warmth. The typical argument is about soft joke cartoons. Hardly any editorial cartoonist conveys warmth in his cartoons. And clearly, as the syndicate guy here, I can see that editors respond to warmth in cartoons.  DARYL: It’s not just cartoons. We also see much more soft and fluffy from columnists on the Op-Ed page. Our most popular columnist is Tom Purcell, who often writes light pieces about life – but his columns about warm remembrances are the most popular by far.

DARYL: It’s not just cartoons. We also see much more soft and fluffy from columnists on the Op-Ed page. Our most popular columnist is Tom Purcell, who often writes light pieces about life – but his columns about warm remembrances are the most popular by far.  When I was younger, I cared a great deal about appealing to editors and my work reflected that. Syndication for me was a big second income. Now it is pocket change, thanks to cartoonists and cartoon marts undercutting the market with cheap, mediocre cartoons. So, I draw cartoons for my paper with the understanding that my readership extends outside the pages of the Ottawa Citizen. I prefer to stick with what my paper desires and I’m fortunate they give me a lot of freedom to do what I do. I draw holiday cartoons; I even draw (gasp!), faith-based Easter cartoons. Fortunately, they haven’t complained yet, but editors change.

When I was younger, I cared a great deal about appealing to editors and my work reflected that. Syndication for me was a big second income. Now it is pocket change, thanks to cartoonists and cartoon marts undercutting the market with cheap, mediocre cartoons. So, I draw cartoons for my paper with the understanding that my readership extends outside the pages of the Ottawa Citizen. I prefer to stick with what my paper desires and I’m fortunate they give me a lot of freedom to do what I do. I draw holiday cartoons; I even draw (gasp!), faith-based Easter cartoons. Fortunately, they haven’t complained yet, but editors change.